The Irresponsibility of Rolling Stone’s “The 100 Greatest Songs in the History of Korean Pop Music”

The editors must ask themselves.

“The 100 Greatest Songs in the History of Korean Pop Music,” published by Rolling Stone on July 20, was deeply flawed. The decision to not separate “K-pop” from “Korean popular music” makes one wonder if the editors compiled this list with sufficient understanding or reporting of Korean popular music, or if they had any self-awareness of their international (i.e. Anglophone) perspectives on Korean music.

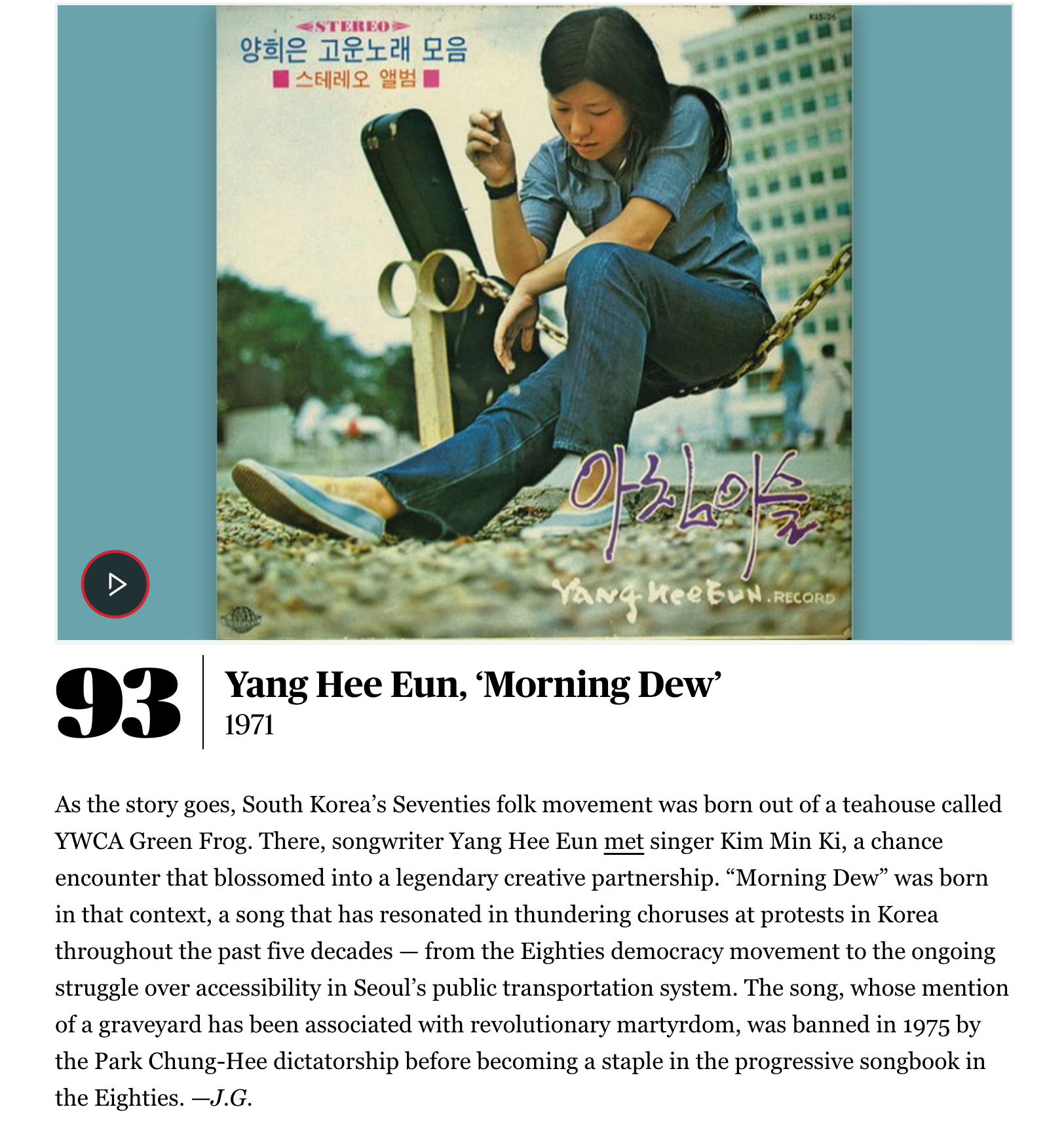

Though the list purports to have “looked beyond the strict definition of K-pop as a hitmaking business in order to tell the broader history of Korean popular music,” it is closer to a cherry-picked list of Korean popular music that centers and privileges K-pop. The 34 non-K-pop songs are nowhere enough to “tell the broader history of Korean popular music.” Artists like the The Kim Sisters, Yang Hee Eun, Han Myung-sook, Shin Hae-chul, Love and Peace, Lee Mija, and Yun Sim-deok, whose careers span most of the 20th century, make sporadic appearances with little context.

Baffling rankings indeed. According to Rolling Stone, the greatest songs in the history of Korean popular music (not K-pop), in order, are ‘Gee’ (Girls’ Generation), ‘Candy’ (H. O. T.), ‘Good Day’ (IU), ‘Spring Day’ (BTS), and ‘Short Hair’ (Cho Yong Pil). ‘Wa’ (Lee Jung Hyun) is now a greater song than ‘Beautiful Woman’ (Shin Joong Hyun and Yup Juns), ‘Tears of Mokpo’ (Lee Nan Young), and ‘Hymn of Death’ (Yun Sim-deok). BIGBANG, 2NE1, Red Velvet, and last year’s debutants New Jeans sit in the upper echelons of Korean popular music over Jang Pill Soon, Deulgukhwa, Nami, Sanullim, and Deux.

The chief point of criticism is neither the fact that K-pop songs make up roughly two-thirds of the list, nor that they are often ranked above certain non-K-pop songs. Had the intent behind certain placements been justified with historical context and explanation, perhaps the list could have been more acceptable. Unfortunately, the best explanation of Korean popular music can be found in the introduction to the rankings, not the individual selections. In the 100 blurbs accompanying the 100 songs, there is a shared and noticeable dearth of historical context and significance of each song.

‘Gee,’ the greatest Korean song of all time, is lauded for its popularity and “dizzying, maximalist aesthetic,” while its historical significance is limited to the group’s rivalry with Wonder Girls. ‘Candy’ is given 2nd place for how it allegedly “set the bar for every K-pop boy band’s sugary-sweet summertime earworms to come.” ‘Haru Haru’ (BIGBANG) is given 7th place for successfully “flipping Japanese deep house into a high-stakes R&B drama.”

Citing its inclusion in Reply 1997 as evidence of the greatness of ‘Chau Chau’ (Deli Spice) while disregarding the album’s critical acclaim throughout the past three decades, and sparing just one line to the song ‘Pierrot Laughs at Us’ (Kim Wan-sun) while trying to cover Kim Wan-sun’s illustrious career are just a few examples of how flimsy each selection is. ‘That’s Only My World’ (Deulgukhwa) carries immense cultural and historical significance that is overlooked in the article in favor of “Jeon In-kwon’s glorious vocals” that “sings about clinging to one’s dreams, despite certain hardship and his own naiveté.” Uhm Jung Hwa’s 30-year career as role model, icon, and pioneer is reduced to “actress and pop idol Uhm Jung Hwa who sang techno-trot’s most iconic anthem” in the blurb for ‘Poison.’

(This is the first time I've heard the genre of techno-trot. Presumably, the speaker wanted to refer to the slang terms for trot in Korean pop songs, "Ppongjjak" and "Ppongki". ‘Ppongjjak’ is also a subgenre of trot that was combined with electronic music in the 2000s. In Korea, the common melody and distinctive singing style of trot is called "Pongki," an attribute that applies to all Korean pop songs, regardless of genre. However, it is not called a trot, and it is a clear error to describe Um Jung-hwa's music as techno-trot. Are Cheongha, Tiara, Britney Spears, and Ava Max techno-trot singers?)

Historical context is close to nonexistent. There is zero mention of how ‘Spring Day’ (BTS) was uniquely situated in the turbulent Korean political climate of 2017. ‘Short Hair’ (Cho Yong Pil) is described as “inextricably associated with the liberatory spirit of the Eighties,” but the May 18 Gwangju Democratic Uprising is not even named, whereas A Taxi Driver, the 2017 film that is based on May 18, is cited as evidence for the song’s significance. Entries for Shin Joong Hyun, Han Myung-sook, and Patty Kim make no mention of the Eighth United States Army, the most prominent element of the United States Forces Korea (USFK), which served as the most competitive and prestigious stage for Korean musicians throughout the 1970s.

Selections from the 1990s underground and independent music scene are sparse and barely explained. The list is misleading at times, referring to Yang Hee Eun as the “songwriter” and Kim Min Ki as the “singer” for ‘Morning Dew,” when in reality the song was written and sung by Kim initially in 1971, and found more popularity once Yang covered it again later that year.

Does this list live up to its professed goal of covering the “plenty of homegrown artists” that “paved the way for K-pop’s popularity and eclecticism” before the international rise of Hallyu? ‘Sorry, Sorry’ (Super Junior) and Super Junior are described as “helping forge the beginnings of K-pop’s Hallyu wave,” but the entry neglects to mention how truly popular the song was internationally, such as how it topped the Taiwanese charts for a whopping 121 weeks (nevermind that lyu means wave in the first place).

The blurb for ‘Gangnam Style’ (PSY), which apparently “helped introduce K-pop to the world” as the first music video to hit a billion views on Youtube, fails to mention that it was the first Korean song to break into top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Billboard Hot 100 has since served as a coveted metric for all K-pop artists. ‘Kung Ddari Sha Bah Rah’ (Clon) allegedly “established a future blueprint for K-pop,” but the editors neglect the pivotal role of legendary songwriter / producer Kim Chang-hwan and the song’s success in global markets like Taiwan.

(Kim Chang-hwan is an integral part of the history of Korean dance music, alongside Shin Seung-hoon, Kim Gun-mo, Noise, Park Mi-kyung, and Clone. He also composed "Pick Me" for Mnet’s Produce 101. But He was sentenced to eight months in prison in 2016 for verbally abusing and assaulting members of the idol group he produced, The EastLight.)

A better prepared article could have served as a useful manual for understanding K-pop and its international success. If the editors had titled the piece “100 Greatest Songs in K-pop History,” they might have been spared this criticism. But this list is a failure, to say the least. Its premise, level of professionalism, selection rationales, and overall rankings are woefully haphazard. Impressions form the bulk of its commentary, as opposed to any meaningful coverage of the “broader history of Korean popular music.”

The editors must ask themselves, Did they make the effort to truly understand the artists and songs they selected? Did they ever consider consulting the dozens of seasoned professionals based in Korea? The result is a sorely lackluster disappointment, compared to the grandeur of their intent. The most glaring omission is the sense of responsibility one would expect when introducing the culture and history of an entire nation to a global audience.

This list is a textbook example of how so-called “music journalists” operate with a superficial view of Korea, a myriad of misunderstandings, and a blatant disregard for proper reporting. These are the “professionals” that cover K-pop for major foreign media.

Admittedly, music journalism has lost much of its influence. Lists like these are also meant to be read primarily for fun, and not too seriously. Yet I see nothing fun about this travesty. It would be a sad day indeed when a foreign music fan, who developed an interest in broader Korean popular music through K-pop, understands Korean popular music through the faulty lens provided by this piece.

Translation : Ho Kyung Jang

![로살리아(ROSALÍA) [LUX]](https://cdn.media.bluedot.so/bluedot.zenerate/2025/11/q5wwqu_202511191147.jpg)

Comments ()